Accidents – Understanding Human Failures

One of the more challenging services offered by C&C Consulting, is investigating workplace accidents and incidents. Initial internal findings are often presented as part of an evolving process. Typically, these initial findings assign a blanket culpability at the feet of the involved parties, including the injured party in many cases often with no challenge as to why their ‘human failing’ contributed to or caused the incident. Labels such as “he is just accident prone” seem to find their way into findings.

Trying to learn lessons following an incident or near miss involves identifying the human errors that lead to the incident or accident and the factors that influenced the path of human error.

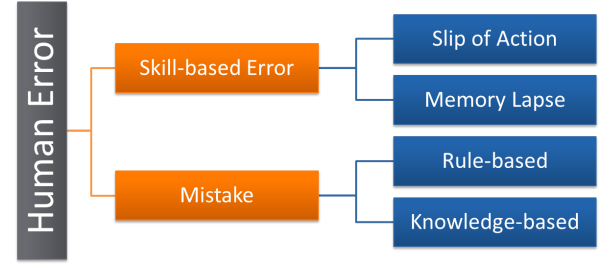

Types of human failure:

It is important to be aware that human failure is not random; understanding why errors occur and the different factors which make them worse will help you develop more effective controls. There are two main types of human failure: errors and violations.

A human error is an action or decision which was not intended. A violation is a deliberate deviation from a rule or procedure. HSG 48 provides a fuller description of types of error, but the following may be a helpful introduction.

Some errors are slips or lapses, often “actions that were not as planned” or unintended actions. They occur during a familiar task and include slips (e.g. pressing the wrong button or reading the wrong gauge) and lapses (e.g. forgetting to carry out a step in a procedure). These types of error occur commonly in highly trained procedures where the person carrying them out does not need to concentrate on what they are doing. These cannot be eliminated by training, but improved design can reduce their likelihood and provide a more error tolerant system.

Other errors are mistakes or errors of judgement or decision-making where the “intended actions are wrong” i.e. where we do the wrong thing believing it to be right. These tend to occur in situations where the person does not know the correct way of carrying out a task either because it is new and unexpected, or because they have not be properly trained (or both). Often in such circumstances, people fall back on remembered rules from similar situations which may not be correct. Training based on good procedures is the key to avoiding mistakes.

Violations (non-compliances, circumventions, shortcuts and work-arounds) differ from the above in that they are intentional but usually well-meaning failures where the person deliberately does not carry out the procedure correctly. They are rarely malicious (sabotage) and usually result from an intention to get the job done as efficiently as possible. They often occur where the equipment or task has been poorly designed and/or maintained. Mistakes resulting from poor training (i.e. people have not been properly trained in the safe working procedure) are often mistaken for violations. Understanding that violations are occurring and the reason for them is necessary if effective means for avoiding them are to be introduced. Peer pressure, unworkable rules and incomplete understanding can give rise to violations. HSG48 provides further information.

There are several ways to manage violations, including designing violations out, taking steps to increase their detection, ensuring that rules and procedures are relevant/practical and explaining the rationale behind certain rules. Involving the workforce in drawing up rules increases their acceptance. Getting to the root cause of any violation is the key to understanding and hence preventing the violation.

Understanding these different types of human failure can help identify control measures but you need to be careful you do not oversimplify the situation. In some cases it can be difficult to place an error in a single category – it may result from a slip or a mistake, for example. There may be a combination of underlying causes requiring a combination of preventative measures. It may also be useful to think about whether the failure is an error of omission (forgetting or missing out a key step) or an error of commission (e.g. doing something out of sequence or using the wrong control), and taking action to prevent that type of error.

When assessing the role of people in carrying out a task, be careful that you do not:

- Treat operators as if they are superhuman, able to intervene heroically in emergencies

- Assume that an operator will always be present, detect a problem and immediately take appropriate action

- Assume that people will always follow procedures

- Rely on operators being well-trained, when it is not clear how the training provided relates to accident prevention or control

- Rely on training to effectively tackle slips/lapses

- State that operators are highly motivated and thus not prone to unintentional failures or deliberate violations

- Ignore the human component completely and failing to discuss human performance at all in risk assessments

- Inappropriately apply techniques, such as detailing every task on site and therefore losing sight of targeting resources where they will be most effective

- In quantitative risk assessment, provide precise probabilities of human failure (usually indicating very low chance of failure) without documenting assumptions/data sources.

CLICK HERE to access a flow diagram on Human Failure Types